© Studio Ghibli

Rather a Pig than a Fascist

Film

Porco Rosso

Year

1992

Director

Hayao Miyazaki

DOP

Atsushi Okui

Country

Japan

Timestamp

00:39:44

22.10.2025

When Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso premiered in 1992, it presented audiences with an unusual protagonist: a World War I fighter ace cursed to wear the face of a pig, living as a bounty hunter in 1929 Adriatic Sea. On the surface, the film appears to be a charming adventure filled with bumbling air pirates, slapstick comedy, and stunning aerial sequences—the kind of lighthearted entertainment one expects from Studio Ghibli. Yet beneath its whimsical exterior lies one of Miyazaki’s most sophisticated meditations on trauma, complicity, and moral courage. The film’s most iconic line—“I’d rather be a pig than a fascist”—has become a rallying cry that transcends its animated origins.

The Meaning of the Pig: Self-Imposed Exile and Moral Clarity

The central mystery of Porco Rosso is the nature of Marco’s transformation. The film offers a superficial explanation—“a curse”—but this doesn’t ring true. As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that Marco’s pig form is self-imposed, a manifestation of his shame, guilt, and refusal to participate in the human world that produced the horrors of war.

The WWI Trauma: The Souls of the Dead

The film’s most haunting sequence occurs when Marco recounts his transformation to Fio, the young engineer who rebuilds his plane. During World War I, just after his friend Bellini married Gina (the woman Marco loves), their squadron was attacked in a dogfight. Marco flew into a cloud to evade pursuers and blacked out. When he awakened, he found himself floating above the clouds in complete stillness.

Then he witnessed something transcendent and terrible: the airmen who had just died in combat—including Bellini—rose out of the clouds as ethereal spirits, their planes gliding upward to join thousands of other aircraft flying together toward heaven. Marco offered to die in Bellini’s place for Gina’s sake, but his plea was refused. He awakened again, flying alone low over the sea, transformed. The pig form represents his self-imposed penance, his withdrawal from the human community whose wars killed his friends.

Marco’s statement “I am meant to fly solo” captures his existential condition. He has rejected humanity not out of misanthropy alone, but because he has seen what humans are capable of in war. The pig is both a curse and a shield—it allows him to remain apart, to refuse participation in the systems that produce violence.

I’d Rather Be a Pig Than a Fascist

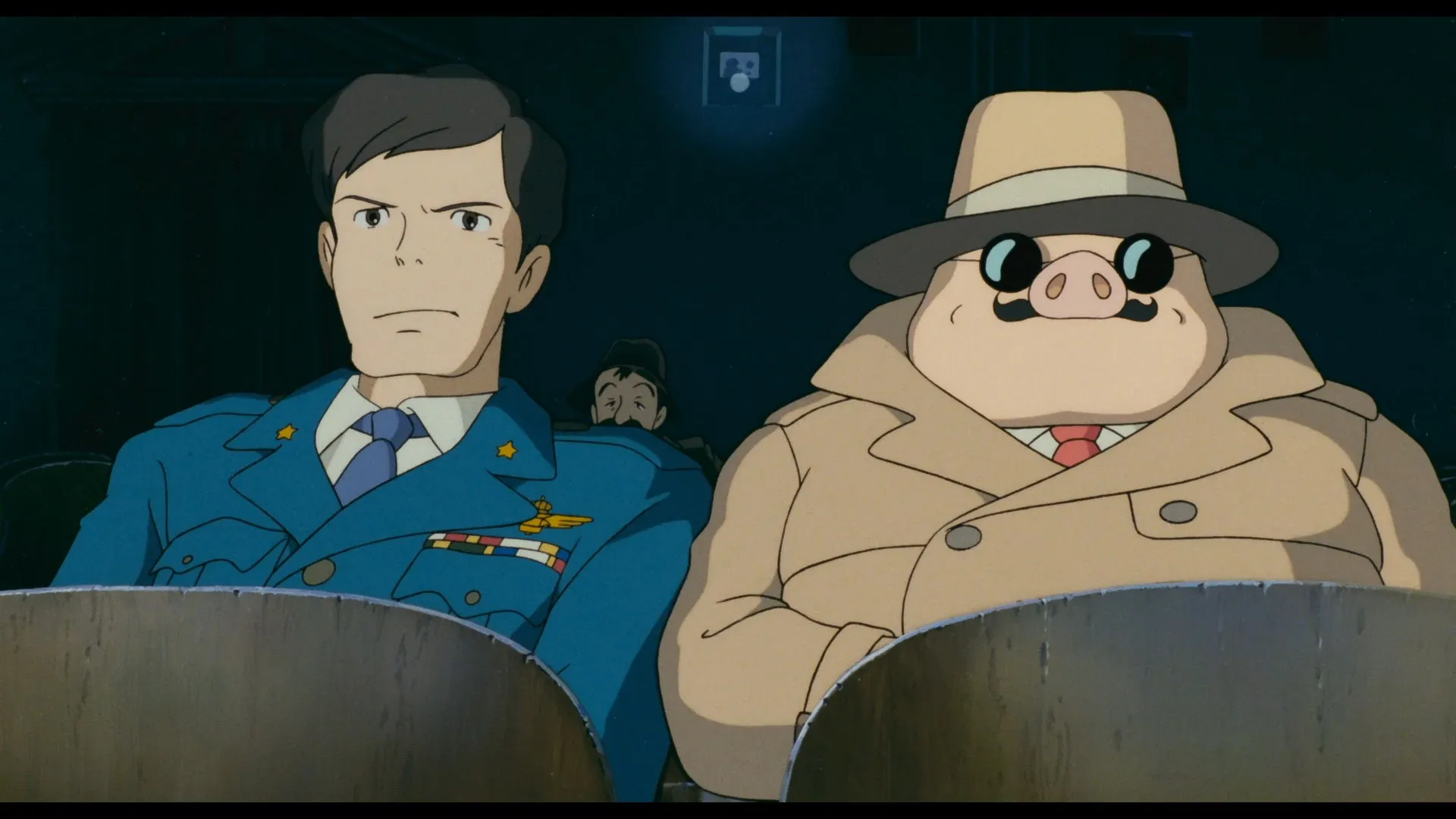

This transformation takes on explicit political meaning when Marco meets his old pilot comrade Ferrarin in a movie theater. Ferrarin, now working with the fascist government, warns Marco that the Italian Air Force wants to recruit him—and refusal is not an option. The fascists have issued warrants for Marco’s arrest on charges of “treason, illegal entry, decadence, pornography… and for being a lazy pig”.

Ferrarin offers Marco immunity if he rejoins the military. He appeals to traditional notions of duty: country, nation, honor. Marco’s response is devastating in its simplicity: “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist”.

This line has become legendary, but its full meaning emerges only in context. Marco follows up with a crucial clarification: “I only fly for myself”—explicitly rejecting the “worthless causes” of nationalism and state service that Ferrarin proposes. When Fio later asks if Marco is a spy, he laughs and replies, “You have to work harder than me to be a secret agent”.

Marco is not a resistance hero in the conventional sense. He is not organizing cells or sabotaging the regime. His resistance is existential refusal—he will not participate, will not legitimize, will not serve. As one analysis puts it, “Instead he proves the absurdity of fascism by showing us a life lived in opposition to it—a life free of bigotry, authoritarianism, and meaningless bureaucracy”.

The pig form thus represents moral clarity achieved through absolute withdrawal. Marco has opted out of the human systems of power and violence. He cannot be recruited, cannot be co-opted, cannot be enlisted in the machinery of fascism because he has placed himself outside the category of “citizen” entirely. As he notes, “I’m a pig. Laws don’t apply to me”.